Where did all these robins come from?

By Melinda L. Lucas

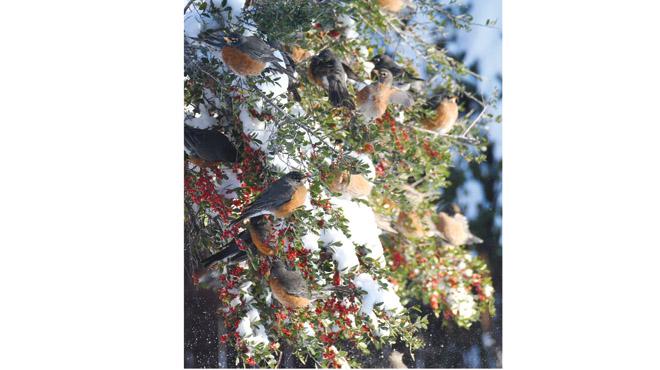

Most people in this part of Texas associate the first sightings of robins with the coming of spring, but in the past week, there have been multiple comments on social media about the hundreds of American robins seen in and around Albany, even as temperatures dipped into the single digits.

Dozens and dozens of the orange-breasted birds have been observed in yards around the community, strutting around on top of several inches of snow and feasting on berries in neighborhood shrubs and trees.

It’s not unusual to see a pair of robins digging for worms in the spring, but is it normal for these birds to travel in large flocks in this kind of weather?

It’s completely normal, according to Elizabeth Howard, founder and director of Journey North.

Journey North’s American Robin project has been tracking robin movements across North America for several years.

Howard pointed out that robins, though considered migratory, don’t follow the typical north to south and back migration pattern associated with other migratory birds. Some robins don’t migrate at all.

If they can find fruits or berries, some may stay close to their summer homes even in fall and winter.

Other robins just move as far as they need to in search of fruit. They might move a little bit and then fly a bit farther south when they need a more abundant supply of fruit.

Apparently, these particular flocks of robins have found an abundance of berries in Albany, Texas.

Howard also said that in the winter, American robins wander in flocks to help one another find food and avoid predators.

“In the wintertime, robins are actually very social,” Howard says. “They form flocks – all those eyes and ears are good for watching out for predators.”

She added that if one or two birds find food, they call the rest.

“Sometimes you see them and it’s so cold you think, ‘My goodness, they’ll all die’.” Howard said. “It’s amazing to see, but the way they survive winter is they fluff their feathers and get really big. Their internal temperature is 104° F and yet they can be in areas below freezing. That’s how well their feathers insulate them; there can be a 100-degree difference just through those layers of feathers.”

Robins favor a winter diet of berries because that’s what is available. As temperatures rise and snow begins to melt, robins will shift their eating habits to earthworms.

“If you want to observe robins in winter, try putting out water for them,” said Howard. “They can survive on their own by eating snow, but birds always welcome a source of unfrozen water for drinking and bathing.”